Wednesday, Jan 27, 2016

Paper published in Cell Systems

A major publication from the Bicycle project is helping to reveal how mammalian cells control transition into the DNA replication phase of the cell cycle. The research published in Cell Systems (1) comes from the ongoing collaboration between the labs of Bela Novak (Oxford) and Chris Bakal (ICR), who are investigators on the Bicycle project together with Francis Barr, Ulrike Gruneberg and Helfrid Hochegger. Postdocs Alexis Barr at the ICR and Stefan Heldt in Oxford are responsible for much of the work carried out for this paper. The research provides a molecular explanation for how mammalian cells transition abruptly and irreversibly into the DNA replication phase. It also provides insight into how other transitions in the cell cycle may be controlled.

Cells control DNA replication through an elaborate set of networks that are similar between yeast and mammalian cells. There are two distinct points that the cell must pass through to enter S-phase (DNA replication phase). The decision to proliferate takes place during the resting (G1) phase of the cell cycle - at ‘Start’ in yeast or the ‘restriction point’ in mammalian cells. The irreversible transition from G1- to S-phase and commitment to replication occurs shortly afterwards.

Cyclins are a family of proteins that are important for driving the cell into S-phase. By forming complexes with the Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), Cyclins promote the activation of CDK activity. Different combinations of Cdk/Cyclins control different transitions within the cell cycle, and the G1/S transition is driven by the activity of Cdk2, in complex with either CyclinE or CyclinA. These Cyclins accumulate as their genes are turned on at the restriction point. However, full activation of Cdk2:Cyclin complexes first requires degradation of Cdk inhibitors (CKIs), such as the p27 protein, which keeps Cyclin:CDK complexes in an inactive state. On top of these controls are feedback loops that ensure that the G1/S transition is both abrupt and irreversible. The dynamic interactions between these different cell cycle components have been well described in yeast but are less well understood in more complex mammalian cells.

The G1/S transition is one of four cell cycle transition points being studied using systems biology approaches as part of the collaborative Bicycle project. As a starting point, the Novak and Bakal groups decided to use HeLa cells to study this transition. Like many cancer cells, HeLa cells do not have an intact restriction point and enter into S-phase directly after cell division. The cells therefore provide an excellent model for studying the G1/S transition. In addition, the G1/S transition is an attractive therapeutic target for preventing cancer cells from dividing.

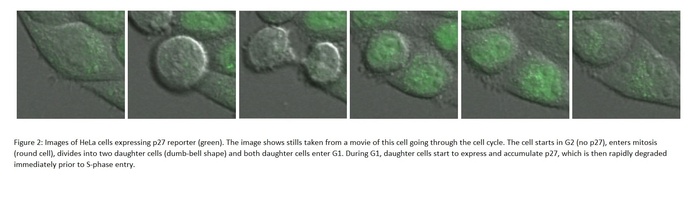

Images of HeLa cells expressing p27 reporter (green). The image shows stills taken from a movie of this cell going through the cell cycle. The cell starts in G2 (no p27), enters mitosis (round cell), divides into two daughter cells (dumb-bell shape) and both daughter cells enter G1. During G1, daughter cells start to express and accumulate p27, which is then rapidly degraded immediately prior to S-phase entry.Up to now, researchers have studied the mammalian cell cycle using synchronized cell populations. The new research uniquely takes a single cell approach, measuring the levels of key regulatory components of G1/S by imaging cells using confocal microscopy. A high-throughput automated system in the Bakal lab allows multiple samples to be imaged at the same time.

‘Single cell analysis is one of the key parts of this study, and it was vital that we took the time to generate and validate the cell cycle reporters, which is technically the most challenging element,’ says postdoc Alexis Barr. Generating these reporters allowed her to image and measure two components in any one cell at the same time and by linking back to a common component, correlate the expression and activity of the key components. To handle the huge amount of data generated, the group also had to develop a semi-automated image analysis pipeline.

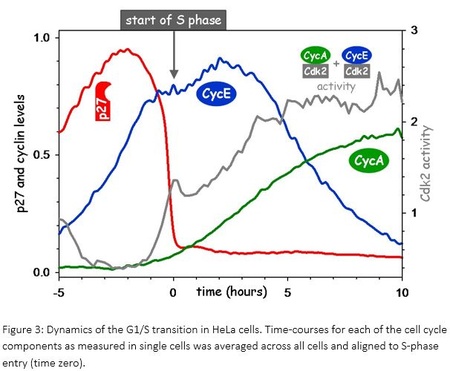

Dr Barr constructed reporters for the Cdk inhibitor p27 and for CyclinA and CyclinE, which form complexes with Cdk2 and activate it, triggering entry into S-phase. She also made a reporter of Cdk2 activity and used PCNA, a component of the DNA replication machinery, as a marker of DNA replication. Once the group had collected the data, they had to average the time-courses for each of the reporters and align the cells to the start of DNA replication.

Professor Novak explains what they saw: ‘When you do this, you see a precipitous drop in p27 levels. It’s like going to the edge of the cliff and dropping off.’ Once CyclinE reached a critical level, p27 could not exist anymore and displayed a very sharp, switch-like drop just as replication started. The genes for both CyclinA and CyclinE are switched on in a similar way, but CyclinA is degraded during G1 so CyclinE accumulates first.

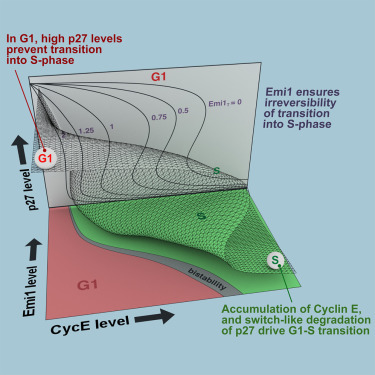

To understand how the activities of the different cell cycle components are related, Professor Novak and his postdocs used the experimental data as they were being generated to develop a dynamic model. Because each cell is different and ‘noisy’, they needed to carry out stochastic modeling. They were able to construct a model of the G1/S transition that suggested that the abrupt degradation of p27 is due to a feedback loop between Cdk2:CyclinE and p27 and that this drives a switch-like entry into S-phase. Dynamics of the G1/S transition in HeLa cells. Time-courses for each of the cell cycle components as measured in single cells was averaged across all cells and aligned to S-phase entry (time zero).

Their model also predicted the impact of another cell cycle component, Emi1, on the G1/S transition: that Emi1 was important in ensuring that the G1/S transition was irreversible. Dr Barr tested this by depleting cells of Emi1 using RNAi and found that, as predicted, G1/S control was lost and cells underwent additional rounds of DNA replication.

Professor Novak explains that an important feature of the G1/S switch is that, like a light switch, it is a bistable switch; it has critical points where it is turned on and off and is ‘cleaner’ than other types of switches. The demonstration, both experimentally and theoretically, that a bistable switch seen in yeast is also present in more complex mammalian cells is a key finding of the research. ‘We want to understand what types of switches are operating in the mammalian cell cycle. Now we’ve used single cells to show for the first time that a bistable switch is operating for G1/S, controlling the activation of Cdk2 by Cyclin E and p27.’

Having focused on cancer cells in this study, the group is now looking at normal cells. The presence of a restriction point in these cells makes the work far more challenging but equally important.

Dr Barr puts much of the group’s success down to the excellent communication between its members despite their diverse scientific backgrounds. ‘We discuss work at least once a week and sometimes every day. This helps us to understand each other’s work and technical problems. As a biologist or mathematician, we make assumptions in our work and it’s good to be able to challenge these.’

Commenting about the novel use of a single cell imaging approach, Dr Bakal says: “We know a lot about the cell cycle from work done mostly in populations, but barely any work has been done in single human cells. Looking at the single cell versus a population is the approach of the future - we have the potential to learn many things about the cell cycle, as well as challenge what we think we know already.’

He highlights a further importance of the work. ‘The mathematical models that we’re building will allow us to find the true points of interventions in cancer cells and design small molecules to target these. By providing us with maps, we will know where in the pathway to strike – up to now, we’ve been guessing this.’

The Bicycle project is funded by BBSRC via the sLoLa research initiative, grant reference number BB/M00354X/1.